In “Law vs. morality”, I used the not-at-all controversial topic of abortion to illustrate why the optimal way to govern—or at least to legislate—is at the most local level possible. In this article, I’m going back to the same well: using hot-button topics like race, Hamas-Israel, and abortion as convenient tools to make a point.

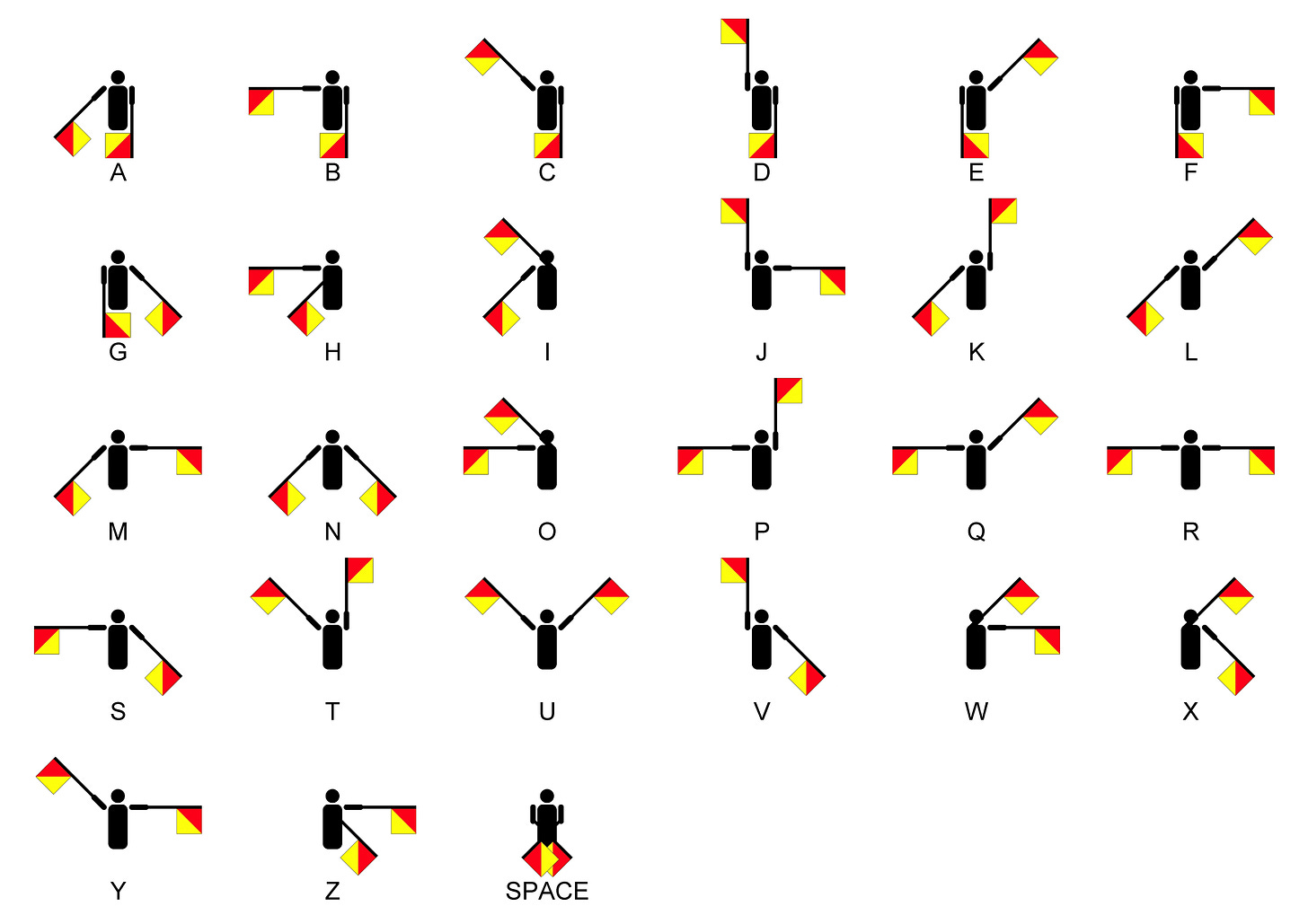

Before the advent of radio communications, the only ways for ships to communicate were visual. There are multiple systems: Morse code (transmitted using flashes of light), the international maritime signal flag system, or semaphore, to name a few:

The reason this works is because sailors share a single “dictionary” of what the signals mean. Because they all refer to the same agreed-upon dictionary, they can use these symbolic gestures to communicate useful information.

More broadly, a defining feature of the human condition is that we can’t (yet) know what’s inside another person’s head. We must rely on a symbolic system composed of sounds we make with our mouths, and a related system of visual symbols we draw on paper that represent those sounds (or combinations of them1), to pass information back and forth. And again: the reason this works is because we have a shared dictionary that we learn as part of learning a language. Without this dictionary, the sequence of sounds (or drawings on paper) is meaningless. With the wrong dictionary, the wrong message may well be received.

Which is why one of the most insidious and nefarious attacks on society as we know it, is the attack on the concept of fixed definitions. Arbitrarily changing the meaning of a symbol—or making the meaning ambiguous—can strip all sense out of a conversation; or worse, it can make the conversation mean different things to different people.

An illustration: black lives matter vs. Black Lives Matter

First of all: damn you, Steve Jobs, for making my iPad autocorrect “black lives matter” to “Black Lives Matter”!2

The statement “black lives matter” is pretty straightforward. Who wouldn’t agree with it? What’s the alternative—that black lives don’t matter? Of course they do. We can all agree with this statement, as we can agree with any statement of the pattern: “<BLANK> lives matter”.3

But who among us has the intestinal fortitude to stand amid a crowd chanting “Black Lives Matter!” and to yell “White Lives Matter”4?

Furthermore, consider this:

Suppose that someone were to ask you “do you believe black lives matter?” A “yes” answer means that you believe black people’s lives are just as valuable as those of any other race.

Suppose instead that someone were to ask you “do you believe Black Lives Matter?” A “yes” answer means you affirm BLM’s philosophy, to include their assertion that “we live in a world where Black lives are systematically targeted for demise.”5

Somewhere along the way, the meaning of those three simple words changed, didn’t it? How do you know whether you are hearing a capital “B”, “L”, and “M”?

Are we murdering babies or decolonizing settlers?

If someone were to ask you: “Is it OK to murder babies?” what would your response be? That’s a largely rhetorical question; I assume I know your answer. Moreover, I’ve stacked the deck through word choice. “Murder” by definition means wrongful and malicious killing—which is bad. A baby is the most innocent and defenseless manifestation of human life—someone we are viscerally, instinctually driven to defend from harm. You are compelled to reply “No, of course not!” Any other answer would be an endorsement of murder (by definition, wrong)—and murder of babies, at that (even more wrong).

What if someone were instead to ask you: “Is it OK to resist against occupation, to expel illegal settlers who are trying to colonize your land?” That changes things just a little, didn’t it? Not only does this action sound justified—indeed, it sounds necessary and even noble.

Which is why you might not see too many pro-Hamas rallies where they explicitly celebrate the murder of Israeli infants during the October 7 raid—but you’ll see more than a few calling for “decolonization” and justifying the killings that took place within the context of a fight for freedom.

And this isn’t just the mask-wearing, Molotov-throwing mob. The “decolonization” euphemism has really caught on, although it long predates October 7; consider, for example, this article from al-Jazeera. For a detailed post-10/7 examination, check out Bari Weiss here. So much so, that even far-right rag The Atlantic felt that they had to offer a different take.

The point is, if we’re not careful and we start throwing around words like “decolonization”, someone might think we’re endorsing the murder of babies. That’s a real possibility these days—I’m just sayin’.

Do you support a woman’s right to choose?

My earlier use of the terms “insidious” and “nefarious” to describe the practice of deliberately slippery meanings was intentional. This particular question—“do you support a woman’s right to choose?”—is a crystallization of the issue; it is the avatar of disingenuous public discourse.

This seemingly simple question is loaded with pitfalls on multiple levels. It’s as much a verbal trap as is asking someone: “so, have you stopped beating your wife yet?”

Individual words

“A woman’s right to choose”. Three words (not counting grammatical necessities like articles and particles), and each of the three is more than a little ambiguous in its meaning. So basically, 100% of the meaning of this phrase is whatever you want it to be.

What is a woman? The difficulty of answering this question is well documented. But let’s set aside the culture-war snark and just focus on the literal meaning of the word. It used to be that “woman” referred exclusively to mature human biological females. Moreover, in the context of abortion rights, “woman” is clearly intended to refer to those women who are pregnant and may want to terminate the pregnancy. However, in the last several years, the meaning of “woman” has broadened significantly; in some cases, it’s become circular: a woman is a person who defines themselves as a woman6. So whose rights are we actually referring to in this case?

What is a right?

Are we talking about a universal, transcendent right, such as those detailed in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights? Because abortion specifically, and reproductive rights in general, are not mentioned in the UHDR.7 Of note, Article 25.2 of the UDHR says: “Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance.” Seems like having children is valued more highly than not having them. So… the UN doesn’t support “a woman’s right to choose”?

Or are we talking about a Constitutional right, codified in our Nation’s founding document and supreme law? See Law vs. Morality for the detailed discussion, but the short version is that no such right is currently recognized to exist within the U.S. Constitution. So… the U.S. Constitution and the U.S. Supreme Court don’t support “a woman’s right to choose”?

Maybe we’re talking about statutory law? There is none at the Federal level, although there could be if Congress passed such a law—nothing prohibits it. So… the U.S. Congress—and the American people whom they represent—doesn’t support “a woman’s right to choose”?

And finally, to choose what? Abortion is an exercise of a woman’s right to control her own body; specifically, whether or not to force her body to go through the process of gestating and delivering one or more baby humans. Let’s not rehash the discussion from Law vs. Morality about the fuzzy grey line separating a fetus from an infant; let’s just stick with “control your own body”. So a woman should have the right to choose what happens to her body. Well and good. Does that extend to vaccines? Does a woman have the right to refuse a vaccine, especially an experimental one? And if so, why do women get this right, but not men?89 What if I am a biological man but I say that I identify as a woman—can I refuse a vaccine then?

The package deal

And even if you could pause the exchange and agree on the meanings of the individual words, the statement “do you support a woman’s right to choose?” is still the conversational equivalent of asking someone to sign a contract they haven’t read yet. Like a Congresscreature signing a bill before reading it—such a thing would never happen!

Saying “no, I do not support a woman’s right to choose” is clearly not a great option—because who wants to say “no, I don’t support women’s rights”?

But saying “yes” signs you up to an unknown commitment. Even if you agreed on basic definitions as noted above, there are still all the additional conclusions—implicit and explicit—to consider.

Suppose one were to respond, “yes, I support a woman’s right to choose”, meaning women should be able to get abortions. OK. When? First month? First trimester? 39 weeks? Where? Special clinics? Any hospital? Who pays for it—private and/or government health insurance? Tax-funded public health programs? What if the mother-to-be is under 18, making her a “girl” and not a “woman”? When does a “girl” become a “woman”?10 Do the parents get notified? Does the father-to-be have any input? What if the mother-to-be identifies as a man—does she still have a “right to choose?” If the “right to choose” is predicated on bodily autonomy, what other rights does this imply with respect to medicine and social policy? Do men get the same implied rights?

The above questions, which I argue are inextricably tied up in any response, are ones I just came up with over ~3 minutes of casual brainstorming. None of them is trivial to answer as it is, and there are many other questions that any reasonably thoughtful person could come up with. The point is, the simple question of “do you support a woman’s right to choose” isn’t very simple at all. By posing it, one lays a verbal trap: either say “no” and be labeled a misogynist, or else say “yes” and agree to a Schrödinger’s box filled with an unknown number of other conclusions and inferences.

It all comes back to pixelated boobs

As I wrote in that article:

[R]eality is messy and complex, but it is also beautiful because of those things. The more we try to simplify it, to gloss over its complexities, to force it to fit neatly into some sort of idealized model—the more of its original beauty and value get lost.

Similarly, the more we try to distill a complex and nuanced topic—like abortion—to a small handful of words with a rudimentary “yes/no” answer, the more meaning we necessarily lose. This loss of meaning, intentional or not, creates a void—a void which must be filled in. And there are no guarantees that when a listener reconstructs the missing meaning, the result will be the same as were intended by the speaker.

See, for example: Japanese kana or Chinese characters. Both systems use a single character to represent an entire syllable or word.

Yes, I know Steve Jobs died years before BLM. But it’s an iPad, so he’s to blame.

NOTE: please do not do this. Or at least don’t tell anyone you got the idea from me.

https://blacklivesmatter.com/about/

See, for example: https://www.npr.org/2021/06/02/996319297/gender-identity-pronouns-expression-guide-lgbtq.

Interestingly enough, one might read Article 16 of the UDHR to mean that the only protected way to marry and start a family is between a man and a woman. Downright regressive!

As long as we’re quoting from the UDHR, Article 2 says “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex…” So applying different rules to men and women would actually seem to violate the UDHR.

And while we’re at it, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination based on sex. Sooo… giving women rights that men don’t have is also against Federal law.

To which question, Stuart Bondek would respond: “One day, we meet!”